Let’s set the stage…

First and foremost, I am a firm believer that the squat should be a part of everyone’s training program. Yes, there are always exceptions, however those are few and far between. The squat is one of the most foundational and functional movements we as humans can do. Think about it. From going up and down from a chair, to getting in/out of cars, to even getting on/off the toilet! We are already performing them on a day-to-day basis, so it makes sense to train it! Not only is it functional, but the overall strength and power benefits are immense. It’s a skill that everyone should master in order to live a healthier, more resilient life.

Here’s the issue. Depending on what you read, you may hear one thing from one source and something completely different from another. There is incredible controversy on what correct squat form should look like. My goal with this post is to dive into some of the biggest squat technique topics and clear some of these muddy waters. Let’s spend the next few minutes together diving deep, so you can confidently master the squat!

Myth 1: Don’t let your knees travel in front of your toes

This became popular among trainers and health enthusiasts in the 80’s with poor research to back it up. It’s less about if and more about when. If the knees translate at or below 90 degrees from the bottom – that’s pretty normal – I’m not freaking out. If they translate early or above 90 degrees, then I’m a bit concerned.

The goal with the squat is to be efficient, straight down and straight back up. If you prevent/ control your knees from advancing forward, you’ll end up with a wavering bar path – not good. If an athlete sits on their heels, and tries to prevent forward translation of their knees over their toes, our squat efficiency plummets. Our knees insufficiently bend and our torso comes forward, which completely throws a clean vertical bar path. From a side view, an inefficient bar is one that shifts forward excessively rather than straight up and down. When we deliberately try to alter the position of our knees instead of going straight down with the lift, as you can imagine, the path gets a little wonky (not straight).

However, don’t initiate the squat with your knees either, just think about:

1. Keeping the heels firmly planted

2. Making sure your weight is distributed in the center of your foot (tripod stance)

3. Keeping the bar path vertical over the center of your foot

Similarly, recent research compared the differences in stress placed upon the knees and hips/low back when performing two types of squats: (1) a regular back squat where knees are allowed to travel forward freely, and (2) a squat that restricted forward knee travel. They concluded that when athletes limit the forward knee travel, it simply shifted the stress from the knees to the hips/low back. The restricted knee travel decreased stress on the knee by 22%…But increased the stress on the hip/low back by 1070%! Which do you prefer?

While decreasing stress on the knees is great, there’s a significant trade-off with the amount of stress placed on the back, greatly increasing the risk of associated low back injuries. So yes, it is true that there is increased stress on your knees during squats if you let them move naturally, however, it’s important to know that this is WELL within the limits of what the knees can handle. Think about this: Did you go up or down stairs today? Well your knees most likely went over your toes… and this (for the majority of the population) doesn’t cause pain.

Lastly, the distance your knees travel over your toes also relates to our morphology, aka the way our bodies were made. The longer our femurs (the big thigh bone), the more likely our knees are to go over our toes. This is fine! Research has proven this to be safe and normal.

Myth 2: Squatting below parallel is dangerous!

This is a big one! We have a couple of options here:

1. Should I bottom out and go butt to heels?

2. Should I transition right at parallel?

3. Should I transition below parallel?

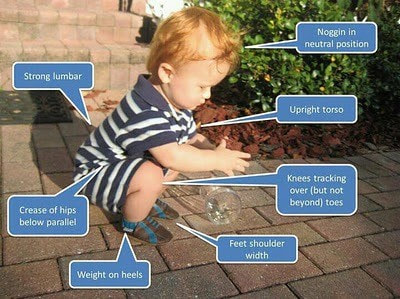

Option #1: Bottoming out and going butt to heels.

Deep squats are natural, age-old positions that people from the non-air-conditioned world still use to this day and are taught to use from birth. They do the vast majority of their everyday activities in a deep squat position. They are working on their natural hip and ankle mobility from a young age, which are major components of the squat. If you measured the ankle dorsiflexion (toes to nose movement) of a baby, you’d see ~70 degrees. Normal dorsiflexion around our parts of the world is ~20 degrees.

Needless to say, humans are born with the ability to squat; some of us just lose the ability when we stop trying. Our strength and mobility are limited because we aren’t taught or forced to use this deep squat. We don’t need it for day-to-day activities like other countries do.

Going butt to heels has the potential to make you expend more energy because of the greater range of motion you’re performing. If you’re looking to increase your strength in a fuller range of motion, then full depth may be the way to go. Usually, athletes can squat more weight when they transition right below parallel because of the lesser range of motion and decreased time under tension as compared to bottoming out.

Highly trained athletes can take advantage of this deep squat position by using the “bounce” out of the bottom to help propel up. However, diving into the bottom of a squat to use that “bounce” is never a good idea unless you’ve trained the back squat using strict full range of motion without the bounce first. Once you’ve built the strength and coordination and have practiced the bounce with integrity, it may be ok to use sparingly. However, one should understand that you’re placing a great amount of stress upon the connective tissues in your joints. The repetitive bouncing out of the bottom, due to the increase in compressive forces in the deep squat, could potentially damage the meniscus and articular cartilage in your knee. Nevertheless, there are currently no guidelines that dictate the magnitude of force that would cause this to happen. Like every other lift or exercise, there are proper mobility drills and progressions that teach body control, stability, and strength. It’s recommended that you practice and train these areas to improve your mechanics and ensure safety before using it.

Option #2: Transitioning right at parallel

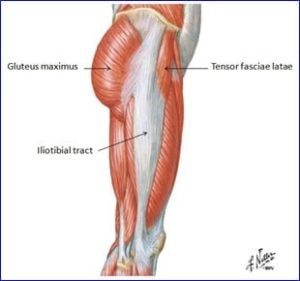

Parallel squats are more quad dominant, meaning there’s a lot more activation from the muscles on the front of your thighs as compared to your glutes. This is because activation of your glutes is greatly influenced by the depth of your squat. Researchers have found that the average muscle activity of the glutes were similar in both a partial and parallel squat, but increased significantly during performance of the full squat. The glute has a direct attachment onto the IT (iliotibial) band, which then attaches to the knee. So your IT band provides more stability to the knee with deeper depths because of the increased contractility from your glutes. When you squat deeper and your weight is centered in your foot, you get activation of not only your quads on the front side of your body but also the glutes/hamstrings on the backside of your body. So the knee is typically more stable because of the coactivation of muscles on the front and back, preventing excessive movement of the structures in the knee.

Similarly, researchers have found that the greatest torque on the knee occurs when you transition right at parallel. Those forces decrease right below parallel. However, even though the torque right at parallel is increased, this is still <50% of the estimated strength capacity of a young healthy persons ligaments. So no, transitioning right at parallel will not blow up your knees. But, transitioning below parallel has been proven to be healthier and safer and is the option I would personally choose to improve the longevity of my joints.

Option #3: Transitioning below parallel.

This is the goal! This is the healthiest, most functional position to achieve. As mentioned above, the forces placed upon the knees are less when you go below parallel. During the deep squat, when performed correctly, your joints are more stable because of the muscular contractions surrounding your knee. This results in less torque, which protects your ligaments and sensitive structures within the knee.

But what if I can’t get down there? If you never go below parallel, then you’ll soon lose your ability to. The old saying holds true… “If you don’t use it, you lose it”.

Taking up squatting all of a sudden can, over time, damage the muscles and cartilage around the patella (the knee cap) in your knee. If you are fit, these muscles remain taut and healthy. But if it unexpectedly has to handle too much pressure, the cartilage can start eroding. Initially, you won’t feel any pain. But eventually it can lead to osteoarthritis, a disorder that is usually irreversible. So it’s important to train and ease your way into the squat. This is done by working on your mobility, working on your strength in those newer ranges, and most importantly, using the appropriate drills and techniques like some of the ones listed below to get you there. Here are some great ones (1st is for hips, 2nd is for ankles, 3rd is for strength).

Myth 3: Having a butt wink is bad!

Let’s start with what exactly this “butt wink” thing is. The squat is a movement that requires motion from multiple joints in the body (hips, knees, ankles, etc). When we squat and use or take up all the available motion from our hips, motion has to come from somewhere else to continue to get deeper. This is where the butt wink occurs. When there’s no more motion left in the hips, your pelvis posteriorly tilts and rotates backwards. This can then disrupt the neutral position of the lower back.

Now let’s talk about a hotter topic…IS THIS BAD? First off – the butt wink is normal! But more importantly (similar to knee translation over the toes), it’s less about if and more about when. If it happens above or right at parallel, we need to work on it. If it happens below parallel, we’re good. Not to worry though, because the butt wink can be improved. Squatting with an early butt wink greatly increase the chance of technique error and injury risk. More specifically, it’s a big contributor to chronically tight lower backs. To fix it, we usually just need to address the most common culprits – hips and ankles. In addition to the awesome exercises listed above, these are great as well.

To simplify things for you guys – just squat! Don’t over think it. If you have pain, change what you’re doing or seek help, if not, then start burying some weight. Don’t worry so much whether you look exactly like someone else while squatting, just simply practice getting your hips lower and keeping your weight over the midline of your foot. If you’re not able to get down there, be patient, don’t push it. Overtime, by working on your mobility and strength, you’ll likely get there. Don’t know where to start or feeling stuck in your training? We, at The Charlotte Athlete, help athletes and active individuals dealing with these same issues. Email us for more information at [email protected] and we’ll get you on the right track!

Thanks for reading!

-Dr. Aerial